31 October - 3 November was the World Fantasy Convention 2013 in Brighton, filled with very good writers saying interesting things to each other about writerly topics. For those who missed it, this series is your own virtual WFC 2013.

|

"Young Adult" (YA) seems to be a growing genre, but perhaps it's only the classification that's growing. Gaiman doesn't remember YA as a genre when he was young. Around 11 or 12 years old, you started trying on different adult books for size; there wasn't that weird thing of books specifically for 11 - 19 year olds. It was an organic progression, says Cooper. As a child, Black always assumed the authors of books were dead. When another book came out, it shocked her. That new books can now get an opening night completely changes what it means to be a popular book. Gaiman suggests that the constellation of Philip Pullman, JK Rowling, and Lemony Snickett changed the shape of the market. Coraline was published in an off-year of the Harry Potter schedule and newspapers were waiting to write about a children's book - and wrote about Coraline. The rising tide that lifts all boats, comments Nix.

Few of the panel set out to write YA fiction: Nix sums up this feeling when he says, "I write for myself and it gets classified as young adult and children's". Hill found the same: he wrote a book with a teenage protagonist; the publishers told the agent it was YA and the agent told him. Cooper's experience is likewise: "I never know who I'm writing for," she says; "They tell me who it's for. Marketing departments label and relabel books. Gaiman remembers reading the Heinlein books as a teenager without realising until afterwards that half of them were the "juvenile" editions. His own children's books usually get two editions, with adult-friendly and child-friendly covers, which sell in a ratio of about 1:2. Black, speaking from her bookshop experience, points out that the YA category is partly an issue of space and browsing within specific bookshop and library sections. In one bookshop, you had to run the gauntlet of towering Disney characters to get to the YA books. Putting the teenagers' books on the other side of that cartoon wall makes a big difference.

Sherman asks what children's books can give you that nothing else can. Gaiman baulks at the definitions: "The worst disease for a publisher is a hardening of the categories," he says. He sees YA as a subset of adult's fiction, rather than children's fiction: books that work for adults and beginning adults.

Black feels that YA fiction has a kind of energy and risk: a crossroads when you're stumbling down the path to becoming a particular kind of adult. Doing things for the first time also makes it a particularly fraught time. Gaiman asks whether YA fiction has to have a teenage protagonist: could you have YA book with a 45-year-old as the main character? Writing with young protagonists, though, gives you three things. First, things are happening for the first time, as Black said. Second, you can write things unmediated. And third, adults, who've lived through more, tend to experience in greys, whereas young protagonists really can have the worst experience ever, and it will be, for them, and the best kiss ever, and it is.

The exact sensibility of YA is hard to define. Nix starts, "They're harking back to more traditional..."

"You mean they have stories," says Gaiman, to laughter. It's not prose for prose's sake, says Nix; the story is king.

That does seem to be one possible feature. Cooper says that 23 publishers turned down one of her books because the protagonist was 11 years old and they didn't know what to do with it. Once she took out the reflective passages, it could be published as a children's book.

Definitions shift, though. When Gaiman gave the first three chapters of Coraline to an editor, they said, "It's the best thing you've ever written, it's fantastic, and it's unpublishable." A horror story for children was unpublishable in 1991. By the time it was published, the publishing landscape had changed. Hill agrees. All publishers want a teen protagonist at the moment, but it will only take one author to push it with a 25 year old and then those rules will change. YA is only partly category, says Nix, and partly marketing ploy: publishers push to categorise a book as YA when it's not, because YA sells.

The YA category does offer freedoms, though. You can do anything, genre-wise, says Nix; it's an all-encompassing category without the restrictions of adult-specific categorisations. Black points out that it's the only genre where we have best-selling poetry. It's not quite a genre, says Gaiman, but it looks enough like one that people let you do whatever you like in there. In any case, genre is largely just a way of telling people where to go in a bookshop. "All it does is tell people where in a bookshop they'll find that stuff."

The genre-blending of YA means that children read outside their expectations. Black has heard kids say they "don't like science fiction" when they lap up YA dystopias. Nix adds that the shelving blends the great variety of YA, which means they can explore more freely. He remembers the impact that certain books had on him, when he was growing up, and wanted to offer the same, to other readers. Gaiman talks about the Yowzer award, given to books for adults that kids would also like, and says he wishes the inverse existed.

One of the criticisms of the YA genre is that it might stop young readers from progressing naturally to harder adult books. Sherman starts to ask if any of the panel have any hard data and Gaiman bursts out bemusedly, "We're authors! We don't know hard data!" He does recall spending hours on Wikipedia looking at the peculiar, non-recurrent bestsellers that pop up: Jonathan Livingstone Seagull, Fifty Shades of Grey, and so on; books that suddenly hit the big time, often through word of mouth from people who don't read much to other people who don't read much. These weird flash-mob books appear inexplicable, seemingly unrelated to any trend in publishing. They may briefly create copycat genres, which often flicker and die - but it's good for the bookshops, at any rate.

Black believes that reading YA fiction can have a positive effect. Some percentage of those children will continue, reasoning, "This gave me a feeling and now I will chase that feeling." She reminds us, too, that these are children who grew up with the release of a book being a major cultural event.

An audience member asks if there's an element of Peter Pan in YA, of not wanting to grow up. Hill says you can write for teenagers without wanting to be a teenager. Gaiman adds that he's just written a novel with a 7-year-old protagonist, The Ocean at the End of the Lane, and he doesn't think it was for people who wanted to be 7. Nix thinks it's the reverse of Peter Pan: most of YA is about wanting to grow up. It's full of discoveries, says Gaiman, especially discovering that adults are flawed, and the world is flawed, and you have to accept that, which is maturity. Asked if young authors (under 20) is a good thing, Gaiman says that books don't get published because of the author's age: it might tip the balance, as a marketing edge, but not much more.

Another audience member, frustrated that YA is considered a "new" thing, reels off a list of 1980s authors writing what was effectively YA fiction, with teen protagonists, and Nix says that a lot of those are now being brought back out as YA. Its popularity as a category is what's new rather than the books themselves.

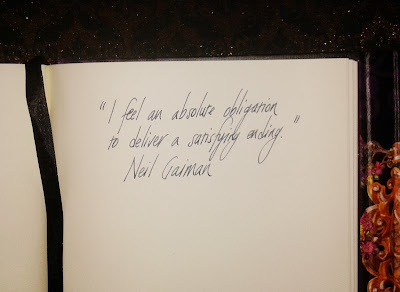

Do people read YA to get back those happy endings, so often missing from adult fiction, especially literary fiction? Black certainly hopes not - some YA endings are very grim! Children's books have happy endings, but not necessarily YA. "I feel an absolute obligation to deliver a satisfying ending," says Gaiman, but that's not necessarily "happy". Another questioner is concerned that the category YA may restrict its readers to reading only that, but the panel has more faith in their readers' independence.

That final audience questioner is right at the back of the vast Oxford hall and inaudible; she's advised to walk forward to ask her question, and does so hesitatingly. "Run!" cries Gaiman. "Run towards us. Scurry, like a gazelle, and shout!"

And the image of a gazelle, at least, offers a happy ending. Provided one doesn't think too much about cheetahs.

Next event in the Virtual WFC: Susan Cooper in conversation with Neil Gaiman.

The virtual conference is created from my own rapid scribblings at the panels and talks and paraphrased - all as accurate as possible, but if you take exception to anything or I've got any details wrong, contact me. Direct quotations are my transcription of someone's exact words as best as I can.

See all posts in the Virtual WCF 2013

Subscribe to the blog at the top of the right-hand bar (check your spam filter for the confirmation email & blog updates) or follow on... • @WritersGreenHse • Facebook / WritersGreenHouse • Google Currents edition